The Unstable Object II (2022)

Directed by Daniel Eisenberg

204 minutes, color, sound, 1080P

Official website: theunstableobject.com

Release Date: July 5–11, 2022

33e Festival International de Cinéma Marseille: fidmarseille.org

Screening:

Videodrome 2 | Friday, July 8 (20H00)

49 Cours Julien

13006 MarseilleCinéma Les Variétés 5 | Sunday, July 10 (14H00)

37 Rue Vincent Scotto

13001 MarseilleCinéma Les Variétés 5 | Monday July 11 (9H30)

37 Rue Vincent Scotto

13001 Marseille

Director’s Statement

I began filming for “The Unstable Object” in 2005, motivated by the kinds of alienation produced by the digital turn, and the palpable shift in the value and relative importance of material things produced by this change. At that time, before the great recession, I was distressed by the vast discrepancies of wealth, power, and resources that I witnessed in daily life... the clearest example of which was that almost all the things I owned were for the most part made in places where workers were disempowered and underpaid. How could I gain purchase on what it meant for those who make these things?

Against the prevailing forces of acceleration, the film’s method employed what I call “durational observation” and attempted to meet the experience of work and labor at the site of production with heightened senses and finely tuned attention; an intentional slowing down of perception and thought.

The Unstable Object II, 2022, extends the issues initially raised in The Unstable Object, 2011 (Prix Georges De Beauregard International, FIDMarseille, 2011). In that first film three specific factories were selected that emphatically isolated one of the bodily senses: sight, touch, and hearing. In The Unstable Object II, 2022 three factories are selected as well, but in the current film, the organizing principle is to trace three radically different constructions of mass and individual at the site of production...

Ottobock

I began the work at the Ottobock prosthetics factory in Duderstadt, where thousands of mass-produced limbs are individualized and customized for a single consumer... and where relatively unskilled labor narrows down to an artisanal engagement with the object... a block of wood is transformed into a lower limb. Here, thousands of prosthetic feet, hands, knees, and other limb parts are produced daily for the world market. Simple, cheap prosthetic feet are produced for the African and Asian markets alongside microprocessor‐controlled joints and limbs for the Global North. On the floor of the high‐tech prosthetics factory the intimate and the anonymous meet. This factory produces limbs that must be individually calibrated to each each surgical procedure, to each geographic location, and to each individual body. These products require a wide network of technicians and specialists to support them, and they must produce as much functionality as possible with the maximum illusion of invisibility.

The factory in Duderstadt is a sophisticated, vertically integrated factory. It has its own wood drying kiln and wood shop, its own forge and stamping facilities, its own machine shop, carbon fiber fabrication, foam production, logistics center, hydraulics and microprocessor preparation, testing facilities, silicone prosthetics fabrication and final fitting clinic. They recycle all but 12% of their energy, recycle all their waste materials, and produced their own software for inventory and distribution for every part that’s produced, down to the smallest screws. It’s uncannily self‐contained.

In visualizing the sheer scale of production at Ottobock, many important questions arise. Why are so many limbs produced daily? What wars, land mines, industrial and vehicular accidents, terrorist events or congenital and medical conditions are invisible yet palpable in these factory spaces? Who pays for them? Who gets the most advanced limbs, and why? What is the relationship between these workers and the final users? These questions, haunting the spaces, are left to the viewer to contemplate while watching the complex interplay of sites, from the wood‐shaping areas, to the alloy parts fabrication shops, to the final fitting of legs and arms... from the mass to the individual.

An arc can be mapped from extremely repetitive, relatively low‐skilled tasks, all the way to highly artisanal, creative craftwork and high‐end technical expertise. The film traces the movement from this mass production to individualized object... ending with the final fitting of a foot for Dominique Bizimana by technical specialist Norbert Jakobi of Ottobock. Bizimana, who travelled to Germany from Kigali Rwanda, lost his lower leg fighting for the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) during the Rwandan civil war in 1994. He has been an Olympic athlete and team captain of the Rwanda Paralymic Volleyball Team.

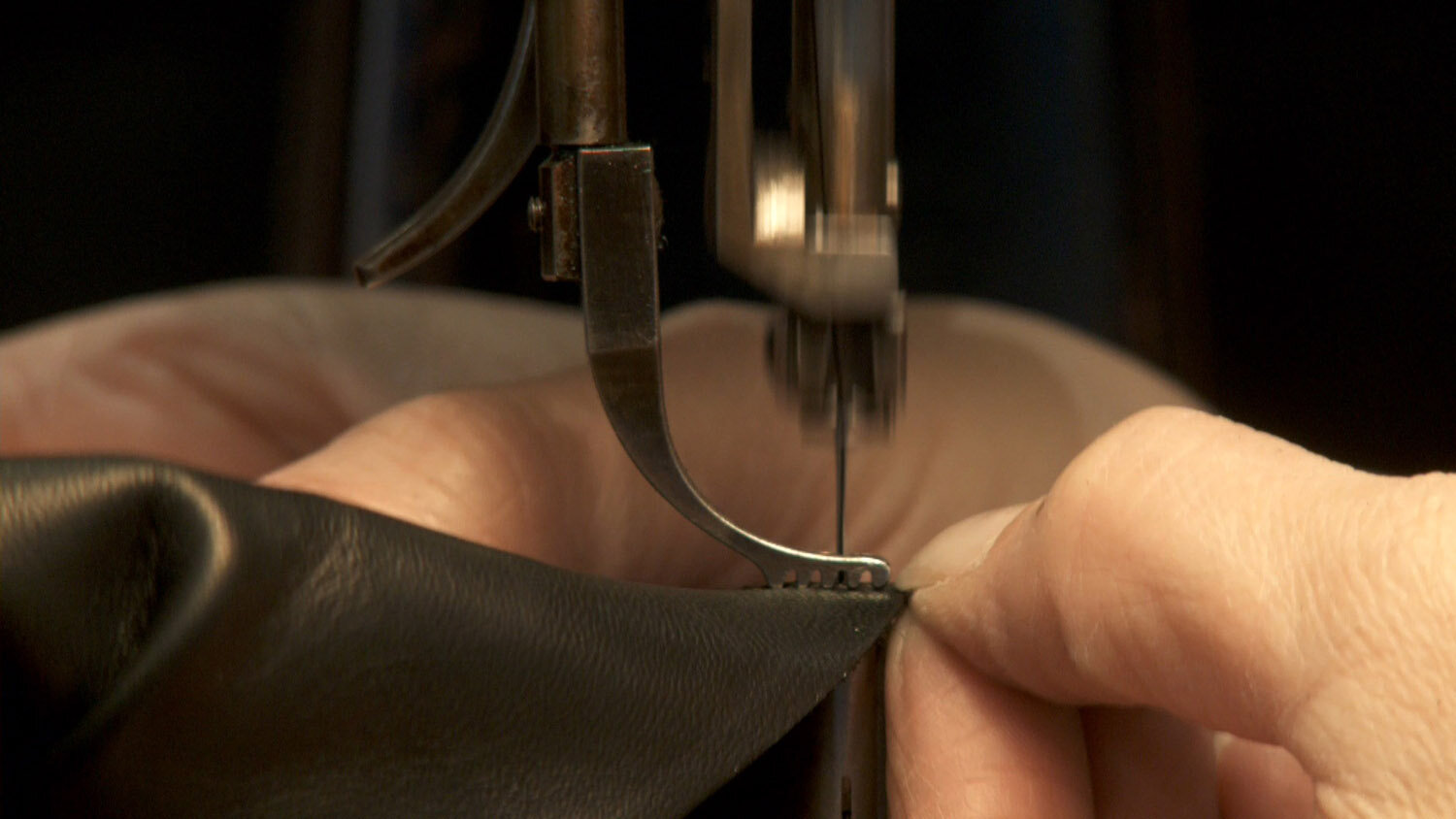

Maison Fabre

The second factory in the film is the atelier of Maison Fabre, a luxury, haute‐ couture glove workshop located in Millau, in the Aveyron department of southern France. Here, master leather crafting has been refined to an art form over centuries, and the relationship of maker to buyer is almost always nearly one‐to‐one, even though international branding, marketing, and the remoteness of point-of-sale obscures and eliminates that one‐to‐one contact. It becomes an anonymous relation, but retains the intimation of intimacy.

The atelier is located in a small part of the original factory, as most hand‐made glove production has been replaced by mass production in large Asian factories, depressing the market for high‐end fabrication. What the atelier in Millau produces are multiple forms of authenticity – some of which are validated by French cultural institutions and ministries, and marketed as an abstract high‐end value. Narrative and history attach to the object. Because of the time it takes to produce the object by trained artisans (who have apprenticed for two years) and their relative scarcity, the gloves produced here are at least three times more expensive than equivalently mass‐produced gloves. Association with designers, fashion houses, and celebrity consumers produce additional marketing value.

Realkom

The third factory in this series, the Realkom factory in Duzce, Turkey, reverses the logic of the Ottobock factory. Here, over 800 employees produce approximately 2000 pairs of distressed jeans a day. Workers spend only seconds with each article of clothing they produce rather than days. Their labor is grueling and repetitive. In this factory a single pair of jeans, designed to look as if one person had worn them over a long period of time, is endlessly reproduced... one individual, mass produced and multiplied.

The uncanny relationship of many hands of anonymous labor producing a seemingly individualized object stands in stark contrast to the work at Maison Fabre. As the consumer acquires the pair of distressed jeans, there is a confrontation: do they indicate time, space and duration by themselves, independently of the consumer? How is the time of natural aging and wear collapsed at the point of production? Are these articles of clothing read as signifiers of individuality and elapsed time? Are they indistinguishable from originally new objects that have been worn down by one person alone? How are they ‘read’?

The film is long… three and a half hours, and I recognize that it may be difficult for some viewers, trained by contemporary media and the constraints of the clock, to slow down enough to adequately appreciate what the film attempts. These forms of labor are destined to disappear in the next few decades, replaced by robots and AI machines. In the future there may be documents of how things were made and perhaps the conditions of labor, but I am quite sure there will be few records of the time of the factory, the social space of daily life, and the subtle relations produced in the working environment.

The film itself is a paradigm of contemporary production… meant to break apart into three separate feature-length films shortly after its initial release as a single, long film. And as material for installation it does yet again something quite different. From a font of original digital source materials, several formal outcomes are produced.

Importantly, I am committed to the formal use of durational observation. While the tendency of most non‐fiction work is to narrow and respond to all these questions I’ve raised with usable information and illustrative images, I believe those tendencies have done precisely the opposite, with tired forms and procedures that often close down thought, and publicly perform unconscious prejudices, cultural biases, and unverified assumptions.

Visual thinking demands we move further and further away from intentions and towards procedures... being fully present at the moment the image is rendered. We are on site for between three and five days... most others, I’m told, rarely schedule more than an afternoon.

I’m neither interested in over‐determining the experience; nor intending a didactic exercise. A return to simpler, non‐narrative, non‐textual forms expand what might be understood from the image of labor. Those images, preserving relations to time and space, retain ontological complexity. They demand analysis and judgment. In these ways it echoes the subjective autonomy required by both citizenship and art.

And those issues of subjectivity remain central. In the worlds of media and film, subjective positioning is classically associated with its cinema-verité roots, so “subjectivity” is often cordoned off from a deeper and more complex consideration, especially when the maker and viewer are both in unchartered terrain. I’m interested in broadening out these questions of subjectivity, because they reflect the wider issues of citizenship, perspective, even empathy and identification... essential aspects of what it means to be contemporary

This project may have become unconsciously motivated and overtaken by its own archival impulses... awaiting future eyes that may redeem these representations of time, space, duration, and social and economic conditions, informing an understanding of that prospective future‐present. But for this project, the work remains simple: find meaningful sites of production, translate experience of them into moving images that somehow convey time, space, social space, and the kinds of attention necessary day in and day out, for those workers who will soon be among the last generations of laborer‐producers.